Is California a Political Casualty in the Hill’s Export-Import Bank Crosshairs?

Whether the lapse in authority for the Ex-Im bank is seen as a concession by Congress to the more ideologically fervent members of a political party’s base, or as others argue, a necessary elimination of government-sponsored cronyism, the future of the Ex-Im bank merits careful consideration. Established in 1945, in the words of its founders, the bank continues to “fills gaps in private export financing in order to bolster U.S. job growth.” What are the likely effects of unraveling Ex-Im, which supported $27.5 billion of U.S. exports, of which close to 90 percent are the products of small businesses and that helped create 164,000 jobs nationwide in 2014? Less often considered in recent debates is the impact a decision not to reauthorize the Ex-Im bank would have at a state level. How would California fare without the Ex-Im bank?In terms of trade promotion, California supports a vast air cargo operation (California airports represent four of the top 16 U.S. cargo airports[1]) as well as five major sea ports (those of Los Angeles, Long Beach, Oakland, San Diego, and Hueneme) that, combined, serve as the primary trade gateway for the entire country. On their own, the San Pedro Bay Ports (Los Angeles and Long Beach) are the largest port complex in the U.S. and eighth largest in the world. In 2010, the value of trade moving through these two ports exceeded $336 billion and supported more than 3 million jobs throughout the U.S.[2]. The value of containerized imports processed at the San Pedro port complex alone exceeded the GDP of a number of countries, including Bolivia, Denmark, Ecuador, Finland, Hungary, Ireland, Israel, New Zealand, and Portugal[3]. With the exporting of goods supporting over 775,000 jobs in 2014[4], what percentage of these jobs associated with trade are leaders willing to concede along with the absence of Ex-Im financing support?

As for the bank’s recent record, Ex-Im boasts a self-sustaining operation that actually returned a $2 billion profit to the treasury over FY 2010-2014. During this period the bank supported the creation of more than 1.3 million jobs.

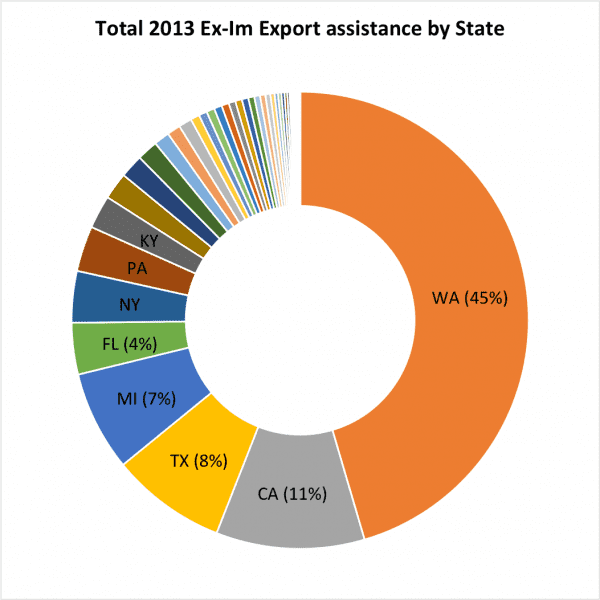

For California, according to the 2013 Ex-Im annual report, of the total $4.9 billion Ex-Im contribution in assistance to exports in the state, 26 percent of these funds were dedicated to export assistance for small businesses. Of a total $20.5 billion in 2014 export financing to states, California’s portion was the second highest in terms of total award and accounted for more than 10 percent of the total.

Source: U.S. Ex-Im Bank

It’s safe to assume that California would be among the states most affected by the closing of the Ex-Im bank, considering: In 2011 one-quarter of all manufacturing jobs in California depended on the export industry[5].

- In 2012, more than 75,000 companies exported from California locations, of which nearly 72,000 were small- and medium-sized enterprises (95 percent of total shippers)[6].

- In 2013, California’s merchandise exports topped $168 billion.

- National tonnage of international trade is expected grow at a rate of 3.4 percent per year between the years of 2007-2040[7].

- Ex-Im supported $211 million in total exports disbursed among eight shippers, five of them SMEs, from 2007-2014, in House Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy’s 23rd District, in the Central Valley).

- In terms of total value, between 2007 -2014, Ex-Im financed $21 billion in California exports, $9.7 billion of which was directed toward small businesses (950 total exporters, 693 of which were SMEs).

The U.S. is not alone in providing bank-supported trade measures. The increasing compliance (Know-Your-Customer requirements) and regulatory (Basel III, Dobb-Frank) burden make it more difficult for SMEs to secure access to trade finance.[8] The World trade Organization estimates that 80 to 90 per cent of world trade relies on some sort of funding. The key element here is that, by definition, international trade must resolve a fundamental dilemma: how to bridge the gap between the exporter’s deadline for payment and the date when the importer is willing to pay. Ex-Im banks are essential in providing solutions to protect both importers and exporters from the risks, such as non-completion or foreign-exchange risk, and to provide means of financing. This is especially true for SMEs or newcomers that would not have the know-how, network or credit worthiness to participate otherwise. In an economy where 98 percent (97percent) of the identified exporters (importers) are SMEs and where SMEs account for more than 50 percent of GDP and jobs, failing to support an Ex-Im bank is equivalent to failing to support economic growth.[9]

California and other coastal states must grapple not only with other foreign export-financing mechanisms, but with increased competition stemming from the expansion and modernization of the Panama Canal and ports in Cuba, Mexico and Canada (British Columbia’s Prince Rupert Port Authority asserts it has the shortest trade route for Asian markets and faster rail access to Chicago). Given the stakes, California leaders should intervene to prevent the death of the Ex-Im bank. California needs the Ex-Im to boost the state’s competiveness, support job growth and provide capital assistance for small businesses. Along with state’s increasing trade with foreign markets comes the expanding national dependence on the movement of goods. Instead of outright elimination, Congressional leaders should reframe the Ex-Im debate around actions needed to boost growth in U.S. exports and support job growth while limiting payouts to big businesses.

[1] Caltrans, Air Cargo Mode Choice and demand Study: http://www.dot.ca.gov/hq/tpp/offices/ogm/key_reports_files/Air_Cargo_Mode_Choice_&_Demand_Study_080210.pdf

[2] SCAG Freight works report: http://www.freightworks.org/DocumentLibrary/CRGMPIS_Summary_Report_Final.pdf

[3] ibid

[4] U.S. Department of Commerce: http://www.trade.gov/mas/ian/statereports/states/ca.pdf

[5] U.S. Department of Commerce, International Trade Administration: http://www.trade.gov/mas/ian/build/groups/public/@tg_ian/documents/webcontent/tg_ian_004048.pdf

[6] Ibid.

[7] U.S. Department of Transportation, Freight Facts and Figures 2013, http://www.ops.fhwa.dot.gov/freight/freight_analysis/nat_freight_stats/docs/13factsfigures/pdfs/fff2013_highres.pdf

[8] ICC global survey (2014)

[9] http://www.sbecouncil.org/about-us/facts-and-data/